- Home

- Roppe, Laura

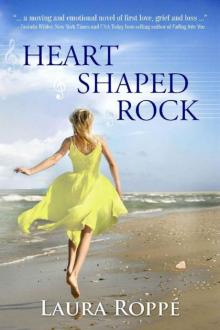

Heart Shaped Rock

Heart Shaped Rock Read online

Heart Shaped Rock

Copyright © 2014

Published by Laura Roppé

Layout by www.formatting4U.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review.

To Brad, Sophie, and Chloe

To Dad and Baby Cuz

To Colleeny

To loved ones far and wide

To loved ones lost, and those left behind

To love, sweet love,

In all its precious forms

May yours endure longer than time

The Music from Heart Shaped Rock

Throughout this story, the characters write and perform songs to express their feelings, often when spoken words just won’t do the job. To listen to the music of Heart Shaped Rock, go to www.LauraRoppe.com, or iTunes. Digital download available on iTunes.

Prologue

I’m not coming down. I grip the tree limb like my life depends on it. The river rushes and crashes and tumbles beneath me.

Her unmistakable voice rises up from the rapids. “Shaynee.”

My heart skips a beat.

“Honey, come on down. The water’s glorious.”

There she is, right below me, wading into the river and grinning like everything’s hunky dory. Her white nightgown billows around her like a halo.

She looks up and smiles at me. Oh God, she’s so beautiful. A lump rises in my throat. I want to smile back at her, but I’m gritting my teeth. I want to yell down to her, to tell her how much I’ve been aching for her, but my throat has closed up. And so, I do the only thing I’m capable of doing, the one thing I’ve become so adept at doing these past months without her—I burst into tears.

Chapter 1

The alarm blares. Six thirty already?

Mom.

I wipe my wet eyes.

I pull on the monkey socks I’d flung onto the floor during the night and shuffle my way across the hall to my brother’s room.

Lennox sleeps peacefully, blissfully unaware of me. His expression is angelic, which is a laugh, considering he’s the devil in Pokémon pajamas. But here in the early morning light, he looks every bit the eleven-year-old cherub Mom believed him to be.

“Lennox,” I whisper, nudging him. Okay, shoving him. “Get up.”

He doesn’t stir.

“Lenn.” I grab his shoulder and shake him. Much harder than necessary.

His eyes flutter open. “I was dreaming of Mom.”

I don’t tell Lennox I dreamed of Mom last night, too. I don’t feel like talking about her this morning. Or any morning. Talking about her being gone doesn’t change her being gone. Today, I just want to pretend to be a normal sixteen-year-old whose biggest problem is a midterm in Art History.

“Get ready,” I say abruptly, turning to leave.

“Shaynee.”

I turn around. Here it comes.

“I miss her so much.”

I sigh. Why does he insist on emoting all the time? Did he not get the memo he’s a boy? Why doesn’t he just go through puberty already and grow a pair?

“I know, Lenny,” I reply, my exasperation evident. I’ve heard all this before.

I stand there, looking at him, deciding whether I should comfort him (again), leave the room, or punch him in the face. The latter two options are my top picks. I’ve comforted Lennox so many times over the past six months, I don’t know if I’ve got any more hugs and soothing words and commiserating nods left inside me. “Suck it up” is what’s on the tip of my tongue these days. Or maybe, if I’m in a particularly polite mood, “Just pretend she’s at the supermarket.” As far as punching Lennox in the face goes, I’m pretty sure it would make me feel a whole lot better, since just the thought of doing it puts an extra spring in my step. But, of course, rather than saying what’s on my mind or doing what my clenched fist yearns to do, I take a step toward Lennox and say, “I miss her, too.” And, boom! That’s all it takes. That horrible pang shoots through my chest yet again.

I sit next to Lennox on the bed and he instantly collapses into me, nuzzling his perfect little nose into my neck.

“I miss her,” Lennox repeats for the eighty-billionth time.

I sigh. For the eighty-billionth time.

“I wrote her a song in my dream,” Lenn mumbles, his voice muffled by my neck. “She cried when she heard it.” He sniffles.

“Well, that’s not saying much.”

Lennox laughs, and I can’t help but join him. Dang, that woman cried easily. Throughout the years, one of our favorite games was “Who Can Make Mom Cry First?” The other was “Who Can Make Mom Laugh First?” Bonus points if you could make her do both at the same time.

To Mom’s credit, though, her tears were almost always tears of joy or pride. “My cup runneth over,” was what she always said when the waterworks started; or, if I’d been singing to her, “You have the voice of an angel.” Mom didn’t cry about the surgeries, or the chemo, or about losing her hair. She didn’t even cry when the doctors explained that her cancer had spread and there was nothing more they could do. “Aw, what do doctors know?” she whispered to me, winking. It was only at the bitter end, when there was no denying the battle was lost, that Mom succumbed to tears of sadness. “I don’t want to leave you,” she sobbed then, clutching Dad’s hand, as Dad, Lenn, and I sat hunched over her frail body on her hospital bed. “If I could stay, you know I would.”

“We know, Mommy,” Lenn assured her, caressing her cheek.

I could see Dad tighten his grip on Mom’s hand, his lips smashed into a hard line. I tried to smile at Mom, to reassure her I understood, to say all the right things, but the corners of my mouth wouldn’t turn up, and words wouldn’t come. Like father, like daughter, I guess.

Lennox sits up from our embrace. “I think I remember the song from my dream,” he says. “I’m gonna work it out real quick so I don’t forget it.” He hops off the bed and lunges toward his guitar in the corner.

“No, Lenn. You’ll make us late for school again.”

“It’ll just take a minute,” he assures me, his fingertips dancing around the guitar frets. “Mom sent it to me.” He strums an E chord and starts humming a melody I’ve never heard before. “Dad can take me to school. He doesn’t care if I’m late.”

Dad doesn’t care about much of anything these days. “Dad’s already at work,” I say, exasperated. Lennox knows this. Every morning for the past month, Dad’s been gone before sunrise, finally back to work, overseeing the construction of a new building downtown. I head to the door. “You’ve got five minutes.”

Lennox ignores me, lost in whatever melody’s playing inside his head.

Great. It’s going to be another morning of dragging Lennox the Walking Emoticon to school. He’s so “in the moment” and “heartfelt” and “good at expressing his feelings,” he makes me want to play Whack-a-Mole on his head. Everyone is fooled by his big brown eyes and sweet voice and otter face, but they don’t have to live with him constantly yammering about his frickin’ feelings. I wish he’d put a cork in it already and let Dad and me just... pretend everything’s fine.

“Hey.” It’s my best friend, Tiffany, a clanking jangle of hoop earrings and bangle-bracelets, bouncing up to me as I put my books into my locker.

Tiffany’s been my best friend since fourth grade, when we both fell deeply and simultaneously in love with Lance Wilson, the fourth-grade equivalent of Justin Timberlake.

“Lance Wilson is my boyfriend,” nine-year-old Tiffany shouted at me on the playground back then (using Lance’s full name on account of his near-celebrity status, sort of like “Robert Downey,

Jr.” or “Neil Patrick Harris,” or, I suppose, “Justin Timberlake”).

“Lance Wilson’s mine,” I whispered back (accepting the first-and-last-name-celebrity-paradigm). I’d been ogling that boy for the better part of the school year (without uttering a single word to him), and, by God, he was mine. In fact, a week before, I’d even written a song on my guitar about him, called “Lance, I Wanna Dance With You.” It rocked. I would have done anything for Lance Wilson—even given him my Hannah Montana lunch box.

“He’s mine,” Tiffany retorted, puffing out her then-flat chest.

“Why don’t you ask him to decide,” redheaded Kayla Ciemowitz suggested from the nearby swings, suddenly inserting herself into the middle of our imminent throwdown.

Tiffany and I looked at each other and shrugged.

We three girls located our prey playing tetherball over by the monkey bars and descended upon him.

“Hi, Lance,” Kayla said, her hands on her hips.

Lance Wilson stepped back from the tetherball pole. “Oh, hi, Kayla.”

Kayla’s eyes twinkled. “You have to decide who you want to be your girlfriend. Tiffany... or Shaynee?” As she spoke, Kayla gestured to each of us on cue as if to say “Door Number One... or Door Number Two?”

I’d never been a prize in the Showcase Showdown before, and my cheeks flushed. Of course, I knew Lance Wilson wasn’t going to pick me. Even in fourth grade, Tiffany already had hella swagger.

Lance Wilson glanced at Tiffany and she did the nine-year-old equivalent of batting her eyelashes. “Hi,” Tiffany cooed, and Lance Wilson quickly glanced away. Lance Wilson then looked at me for the first time in the history of the school year. I blushed, and his eyes left me. Then, Lance Wilson looked at Kayla, and he didn’t look away. In fact, he turned his entire body toward her, not just his face.

Their eyes locked.

They smiled at each other.

Game over.

I wanted to run away, but my feet were stuck on the asphalt in my High School Musical sneakers.

“You wanna play tetherball?” Lance Wilson asked Kayla, jerking his head to the side to whip his long bangs.

“Sure,” Kayla replied, twirling one of her red curls on her finger. She stepped toward him, bumping my shoulder like a linebacker as she passed by.

Tiffany gasped. “You can’t pick Kayla.”

But Lance Wilson and Kayla, now happily engrossed in a romantic game of tetherball, had entered their own world and shut the door behind them.

Tiffany, my former rival, now turned to me, her co-loser in the game of love, and said, “You wanna play two-square?”

I nodded.

She grabbed my hand. “He can go to h-e-double-hockey-sticks.”

“I’ve got some great news,” Tiffany exclaims, jostling me and bringing me back to the present. “Smelly Steven quit Sheila’s yesterday, and Sheila asked if I know someone for the job. Can you believe it? We could work together.”

Sheila’s is the not-ironically-named hipster coffeehouse down by the beach that hosts weekly open mic nights for singer-songwriters—or so I hear from Tiffany almost every day. I’ve never actually been to Sheila’s, but ever since Tiffany started working there a few months ago, she’s been nagging me to come down and check it out. “I make a mean cappuccino,” she always teases. Or, if she’s feeling particularly pushy, she might try the seemingly casual suggestion “Maybe you can play one of your songs at an open mic night?”

“I have no way of getting down there,” I used to say; but since I turned sixteen a month ago and Dad gave me Mom’s car to drive, that excuse doesn’t hold water anymore. The truth is I’m not interested in visiting Tiffany at a coffeehouse. Why would I voluntarily subject myself to a room full of hipsters in skinny jeans, pondering the meaning of life? Or, worse, angst-ridden, teenaged songwriters, pouring out their bleeding hearts about their trivial, pubescent tragedies? What could possibly be so heartbreaking for these normal kids? Running out of Clearasil? And, as far as me performing at an open mic night, I haven’t even touched my guitar since Mom died, so it’s not gonna happen.

“No, Tiff,” I say, but she’s not listening.

“If you don’t swoop in to save me, some other smelly guy—Smelly Sam or Smelly Scott or whoever—is gonna swoop right in.” Tiffany gives me her best puppy dog eyes. “How ‘bout I text Sheila and say you’ll come down there today?”

I consider the situation. The chance to earn a little extra gas money is an attractive proposition, hipsters and teenagers-with-super-important-problems notwithstanding. I’ve gleaned from hushed conversations I wasn’t supposed to hear that Mom’s medical bills were pretty steep during the last year, so I’d like to help out. And, I must admit, it would be ridiculously awesome to work with Tiffany. No matter how much time we spend together, I never, ever get sick of her, even when I’m third-wheeling it with her and her boyfriend, Kellan.

“Okay,” I relent. “Just tell her I’ll come meet her.”

Tiffany squeals and hugs me again, her accessories clanging noisily. “Yay, Shay-Shay. This is gonna be amazeballs.”

Chapter 2

Sheila’s sits on the busiest thoroughfare in Pacific Beach, the coolest and most classically “Southern California beach community” area of San Diego—one street over from and overlooking the bustling beach boardwalk. The building façade is painted electric blue, and terra cotta planters filled with sunflowers hang from the roof’s perimeter. Subtle, Sheila’s is not.

“Okay, so, don’t forget,” Tiffany coaches. We’re sitting in her VW Beetle in the parking lot. “Sheila’s sort of a no-nonsense type, so just smile and answer her questions. No babbling.”

I look at her as if to say, You don’t know me at all.

Tiffany laughs. “She’s gonna love you.” Tiffany gestures wildly and her bracelets clank noisily. Good God, the girl is a one-woman drum line.

I pull a hair-tie from my wrist and smooth my blonde hair back into a ponytail in one practiced movement. “I’m just here to meet her. No promises.”

Tiffany smirks. “Okay, Peaches.”

We enter the front door of Sheila’s, and I’m struck by how crowded the place is on a Wednesday afternoon. What’s everyone doing here?

A long glass counter displaying pastries and muffins sits along the right-hand wall. A small, slightly raised wooden stage sits in the back corner, currently empty except for a microphone stand. Everywhere else, small tables, overstuffed chairs, and a mismatched assortment of cane-back chairs—currently occupied by every variety of surfer, hipster, hippie, yuppie, and artsy type—fills every cranny of the place. Amid it all, a woman in her late thirties or early forties stands behind the counter at a large espresso machine, steaming milk in a metal pitcher and laughing at something a nearby kid has said.

A dark-haired surfer dude about my age wearing board shorts, a shark-tooth necklace, and nothing else saunters toward Tiffany and me, heading to the front door. As he approaches, he looks right into my eyes and flashes me a wide smile, as if I came here just to see him. His smile’s so disarming, and his bare torso so distracting, I glance down. When I look back up, his smile has widened, if that’s even possible.

“See ya later, Jared,” Sheila hollers at Shark-Tooth Boy’s back, and when she catches sight of Tiffany and me at the door, she yells, “Oh hey. Come on in, girlies.”

Tiffany hasn’t stopped holding my hand since we walked in, and now she drags me to the edge of the counter. “Sheila, this is Shaynee. Remember, I told you about her?”

“Gee, let me think,” Sheila says, her tone clearly mocking. “You’ve only mentioned her four hundred eighty-two times since you started working here.” Sheila winks at me. “Welcome, Shaynee-girl.” Before I can reply, she turns her back to me and begins foraging through a drawer. “Here you go,” she says, turning back and placing something in my open hand. “I hope I spelled it right.”

I look down in my hand to find a nametag imprinted with “SHAYNEE” in gold

lettering. There’s a little heart at the end of my name.

“Well, don’t just stand there acting like a potted plant, Tiffany. Grab our girl an apron and get to work.”

Tiffany laughs. “Yes, ma’am.” She lets go of my hand and flits off to a room in the back.

“Ever work an espresso machine before?” Sheila asks me.

I shake my head.

“A cash register?”

I shake my head again.

“Ever earn an honest buck in your life?”

I shake my head a third time.

“Okay, I’m sold. You’re hired.” She winks again.

Note to self: Sheila’s a winker.

Tiffany returns wearing a bright blue apron with “Sheila’s” printed in white letters across the chest. Her nametag forcefully declares “TYPHANI” in glittery purple letters.

Tiffany hands me a blue apron just as Sheila breezes by, toward the front door. “I’m going to taste some beans from a potential new wholesaler. Will you two ‘woman’ the store for me? Tiff, you can teach Shaynee all there is to know while I’m gone.” She looks at me deadpan. “It’s rocket science, Shaynee, so pay close attention.”

“Sure thing,” Tiffany says with confidence. “See you later, Sheila.”

Sheila exits the front door, shouting, “Be good” to no one in particular. A chorus of “Bye, Sheila” and “See ya later” follows her out the door.

What the hell just happened? Did I just get a job?

For the next hour or so, Tiffany—or shall I say Typhani?—scrambles to fill a heavy and diverse stream of drink orders. I try to help Tiffany as best I can, but I have no idea how to work the machine, or the cash register, or even the broom-and-dustpan-in-one contraption. For now, I’m relegated to fetching extra milk cartons from the refrigerator, refilling the half-and-half and cinnamon canisters, serving pastries onto little doily-covered plates, and bussing the tables of empty mugs.

Heart Shaped Rock

Heart Shaped Rock